Untitled [Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A) 1996] 2003

Text by Khwezi Gule - (this is an excerpt of the original text published in the catalog) -A work of art acts as a focal point for intersecting webs of explicit and implicit dialogues. Art is not the creation of one individual. It is a social product. It is social in its conception; in its commission and it its reception. The artist, informed by intuition and experience brings into sharp focus these dialogues through her labour.(...) - Recently other artists have challenged the sanctity of the artist's individual creativity by parodying the work of other artists. Yinka Shonibare has appropriated the images of 18th Century painters and re-inscribed them with new meaning or rather exposed their hidden meanings. But seldom has an artist appropriated the work itself or parts of it in order to make something similar and yet so completely different. Such is Georgia's work in relation to the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres.- American artist Felilx Gonzalez -Torres conceived of the original work when his lover, having contracted HIV began to lose weight. In trying to conceptualise how this gradual process could be brought home to his audience, he came up with a novel idea: to put a pile of sweets equivalent in weight to the body of his lover, to be 'consumed' by the gallery audience. Georgia's own symbiotic/parasitic engagement with the work of Gonzalez-Torres began when she started removing sweets, one at a time, from his installtion at the Art Institute of Chicago.- As Georgia says she produces "not site-specific work but audience-specific work." In this regard the audience is not longer passive observers but active participants, physically and emotionally, in the making of the artwork. Similarly the gallery space no longer consittutes the four walls that contain the artwork but is par of the work itself, part of the dialogue. By extension the histories hidden and overt that the viewer brings along also become part of the texture of the work-inprogress. What is so important about this in the context of the disease, of globalisation and the art world? How do these dialogues come together? - In answering these questions, it is necessary to think back to the recent past. In the 80's and early 90's many images produced to create public awareness of HIV/AIDS featured disturbing images. They were able to achieve, but to disastrous effect. These images, it has been argued, aroused in the general public a fear of HIV positive people rather than inducing a change in behaviour; a fear that caused discrimination against people with HIV. We have seen people shunned by friends and family, viciously attacked, denied social services like medical care because of their HIV sttus. Now, it would be quite a leap of reasoning to suggest that images have the power to kill. But, in so far as a certain cultural consciousness can lead to stigmatisation of people, image-makers have to take their share of responsibility for that culture.- One of the issues that HIV positive people have fought against is the equation of HIV and immorality. There is a recognition that AIDS is a medical problem not one of morality. As the social and economic implications of the virus begin to be felt the issue of HIV/AIDS is being recognised as a human rights issue. In most countries there is a distinction between first generation rights and second-generation rights. First generation rights include the right to vote, right to free speech, etc., which it is considered the State's duty to uphold and provide. Then there are second-generation rights, which are things like the right to education, tomedical care etc., which the State provides but cannot (or doesn't want to) guarantee. The campaigns of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and other HIV/AIDS lobby groups have challenged this logic. They have also challenged the intellectual property rights of pharmaceutical companies by advocating the manufacture of generic medicines. With the shift in emphasis from purely cautionary messages are being heard. These organizations have also challenged patriarchal relationships between men and women as a way of arresting the spread of the disease.- The work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres is subtle and more intimate manner of talking about the effects of HIV/AIDS and is born out of the need to put a human face to the disease. While Gonzalz-Torres locates his work strictly within the cause of HIV, Georgia wants to expand the original parameters of the piece of many fronts. She challenges the authorhip implied by copyright laws, she like the TAC wishes to test the boundaries between ownership and public responsibility. On the other handGeorgia's involvement of her fellow peers in this act of appropriation, reinforces the social and collaborative aspect of her work. - These is an even wider influence in that the piece now exists in different forms across continents. The dislocation that comes with migrancy from one country to another has given her an itnernational sight as to how culture infects other cultures, not unlike the virus itself. Similarly, Georgia's intervention challenges the limits of art making/ aesthetics, the conceptual dimensions of spaces like galleries as well as audience engagement. There is also a playful yet obsessive cimension to the piece. The act of collecting pieces of candy, in adition to the act of presenting the correspondence between the owners and herself recording the contributions of her accoplices, the writing of the number of each specific piece of candy, all 8741 of them, requires some single-minded diligence. - If art is the contribute positively rather than negatively to how people perceive and respond to the disease and its effects,a differen language needs to be employed. Like the HIV/AIDS awareness images mentioned above, much of contemporary art practice suggests that if a work of art is to be effective is must have impact. Impact by any means necessary. It must be either enormous, or shocking/unsettling or made with the most latest state-of-the-art gadgetry. Rarely is a work of art made with sensitivity and subtlety.- There is nothing more disarming than a pile of sweets. Further ivnestigation would reveal however, that this apparent sweetness lies a more ominous tale. As Georgia herself states: "I believed and still do to the metaphor of the body to the point; I cannot bring myself to eat the candy." In an industry where being on the cutting edge in more valued, artworks that deal with emotions such as empathy are marginal. Our engagement with the piece cannot be distant and disinterested. We have to participate, physically and emotionally. It's a profound message that does not seek to influence us through impressive display but through that part of ourselves that enables us to feel and give us a sense of community. Georgia's piece is not intended to leave you shaken but touched.

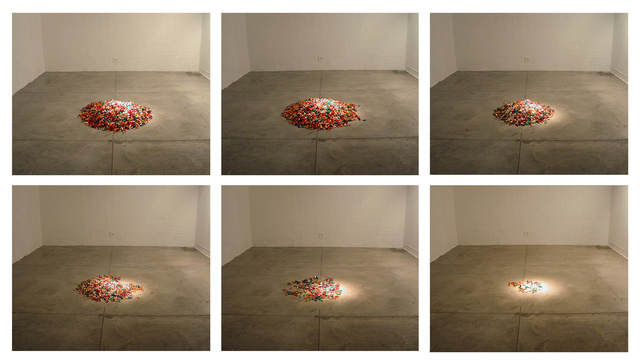

Detail of the work

Opening night

Over the period of three weeks

Unlike the original piece , the candy at the NSA Galley in Durban was not replaced.

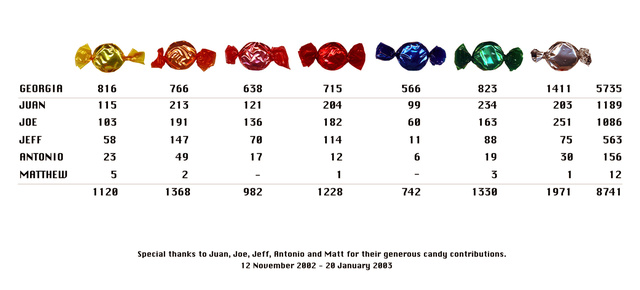

Chart acknowledging the accepted contributions by my peers

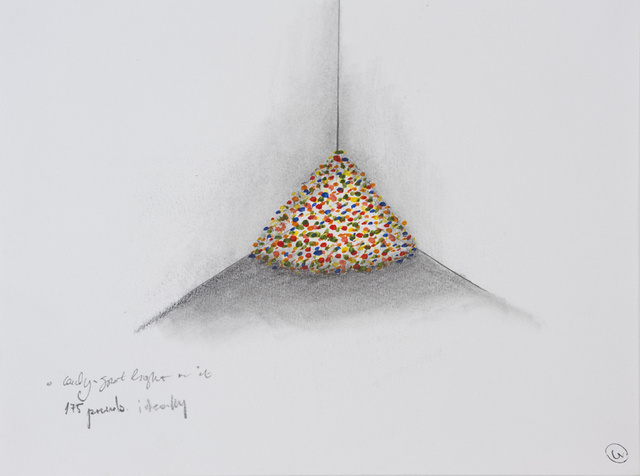

Initial drawing of the original piece

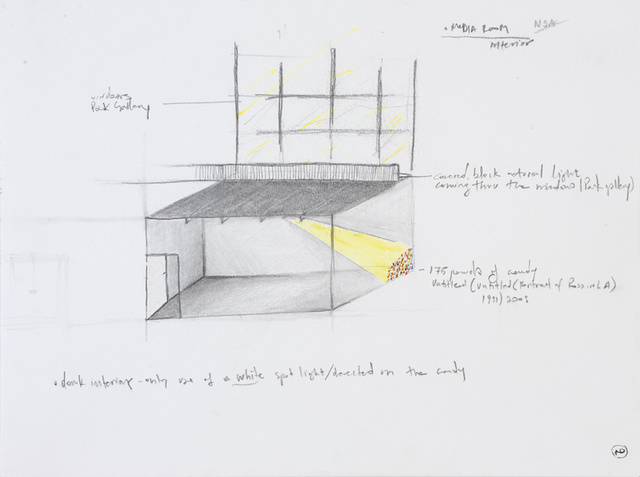

Installation drawing for the NSA Gallery